On this page:

- What is aphasia?

- Who develops aphasia?

- What causes aphasia?

- What are the types of aphasia?

- How is aphasia diagnosed?

- How is aphasia treated?

- What research is NIDCD supporting on aphasia?

- Where can I find additional information about aphasia?

What is aphasia?

Aphasia is a disorder that results from damage (usually from a stroke or traumatic brain injury) to areas of the brain that are responsible for language. For most people, areas in the left side of the brain are affected. Aphasia impairs the expression and understanding of language, as well as reading and writing.

Who develops aphasia?

Most people who have aphasia are middle-aged or older, but anyone can develop it, including young children. About 2 million people in the United States are living with aphasia, according to the National Aphasia Association. People with progressive neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia, may also develop aphasia.

What causes aphasia?

Stroke is the leading cause of aphasia. According to the National Aphasia Association, approximately one third of stroke survivors have aphasia. A stroke occurs when a blood clot or a leaking or burst blood vessel stops blood flow that carries oxygen and nutrients to brain cells. Sometimes blood flow to the brain is only temporarily blocked but then begins to flow again. The terms “transient ischemic attack” (TIA) or “mini stroke” may be used to describe this temporary condition. Language abilities may be affected for a few hours or days after a TIA but are usually not permanently affected.

Aphasia can appear suddenly, following brain surgery or after a head injury, or it can develop gradually from the effects of a brain tumor (and associated treatments). Other causes of aphasia include brain infections.

Aphasia may co-occur with speech disorders such as dysarthria or apraxia of speech.

What are the types of aphasia?

Aphasia from non-progressive causes, such as stroke or other brain injury, is most frequently described based on categories and subtypes associated with stroke. Most often, aphasia is divided into two broad categories: fluent and nonfluent. Wernicke’s aphasia and Broca’s aphasia were the first subtypes identified within these two categories.

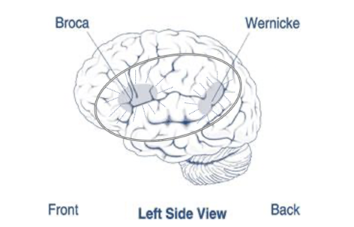

Damage to the temporal lobe (a part of the brain involved in hearing, speech comprehension, and other tasks) may result in Wernicke's aphasia (see figure), the most easily recognizable type of fluent aphasia. People with Wernicke's aphasia may speak fluently in long, complete sentences that have little meaning, adding unnecessary words and even making up words. As a result, it is often difficult to follow what the person is trying to say.

For example, someone with Wernicke's aphasia may say, "You know that smoodle pinkered, and that I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before."

People with Wernicke's aphasia are often unaware of their spoken mistakes. Another hallmark of this type of aphasia is difficulty understanding language, whether spoken, written, or signed.

The most recognizable type of nonfluent aphasia is Broca's aphasia (see figure). People with Broca's aphasia have damage that primarily affects the frontal lobe of the brain—the area behind the forehead. Broca’s aphasia may co-occur with apraxia of speech. Because the frontal lobe also controls voluntary movement, people with this type of aphasia may also have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the arm and leg. People with Broca's aphasia frequently speak in short phrases produced with great effort. They often omit small words, such as "is," "and," and "the."

For example, a person with Broca's aphasia may say, "Walk dog," meaning, "I will take the dog for a walk," or "book book two table," for "There are two books on the table." People with Broca's aphasia typically have an easier time understanding language compared to people with Wernicke’s aphasia, but they still usually experience some degree of difficulty with spoken, written, or signed language. People with Broca’s aphasia are usually aware of their speaking difficulties and can become easily frustrated.

There are other subtypes of aphasia. For example, global aphasia results from damage to extensive portions of the language areas of the brain (see the circled area in the figure). People with global aphasia have severe communication difficulties and may be extremely limited in their ability to produce and comprehend language. They may be unable to say even a few words or may repeat a limited set of words or phrases. They may also have trouble understanding simple words and sentences, whether spoken, written, or signed.

Conduction aphasia is a fluent aphasia in which a person has difficulty repeating words and simple phrases. While their fluency, ability to express themselves, and ability to understand others is better than people with Wernicke’s aphasia, they still often have deficits in those areas.

Other subtypes include transcortical aphasia (motor, sensory, or mixed), anomic aphasia, very mild or latent aphasia, and mixed or unspecified presentations of aphasia.

Different terminology is used to describe progressive causes of aphasia. When people have dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, or other types of dementia) that includes significant cognitive or behavioral changes, they may also develop aphasia as their disease progresses and begins to affect the language areas of the brain.

In some cases, aphasia will be the first and most noticeable symptom of dementia, rather than memory, behavioral, or movement changes. This is called primary progressive aphasia, or PPA. PPA worsens over time, causing the person to eventually lose their ability to use language. As the disease progresses, other cognitive, behavioral, and movement symptoms will emerge.

PPA can be caused by different types of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy Body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. Some subtypes of PPA are associated more commonly with particular types of dementia, but there is still much to learn about these relationships.

How is aphasia diagnosed?

The doctor who treats a person for a brain injury, such as a stroke, may be the first to identify aphasia. Likewise, PPA may be identified by the physician who diagnoses a person with a progressive disease. Most individuals with suspected aphasia or PPA will have undergone a diagnostic scan that may confirm the presence and location of brain injury or brain degeneration. A doctor may also briefly test the person's ability to understand and produce language, assessing the ability to follow commands, answer questions, name objects, and carry on a conversation.

If the doctor suspects aphasia or PPA, the patient should be referred to a speech-language pathologist for a comprehensive examination of the person's communication abilities.

How is aphasia treated?

Following a non-progressive cause of aphasia, such as stroke or other brain injury, tremendous changes occur in the brain that may help recovery. As a result, people with aphasia can often experience dramatic improvements in their language and communication abilities in the first few months, even without treatment. But in many cases, some aphasia remains following this initial recovery period. This condition is called chronic aphasia. Throughout all phases of recovery, speech-language therapy will help patients regain and improve their ability to communicate.

Research has shown that language and communication abilities can continue to improve for many years after the brain injury and are sometimes accompanied by new activity in brain tissue near the damaged area. Factors that may influence the amount of improvement include the cause of the brain injury, the area of the brain that was damaged and the extent of the damage, the age and health of the individual, and access to therapy.

Aphasia therapy aims to improve the ability to communicate by helping individuals use their remaining language abilities, restore language abilities as much as possible, and learn other ways of communicating, such as through gestures, pictures, notebooks, and/or electronic devices.

Technology is providing new tools for people with aphasia. Virtual meetings with speech-language pathologists provide patients with the flexibility and convenience of receiving therapy in their homes through a computer. Speech-generating applications on mobile devices such as cell phones and tablets can provide alternative ways to communicate.

Participating in activities such as book clubs, technology groups, choirs, and art and drama clubs can help people with aphasia regain their confidence and social self-esteem, in addition to improving their communication skills and overall well-being. Stroke clubs (regional support groups formed by people who have had a stroke) are available in most major cities. These clubs can help individuals and their families adjust to the life changes that accompany stroke and aphasia.

Family involvement is often a crucial component of aphasia treatment because it enables family members to learn the best way to communicate with their loved one. A strong therapy program will include communication partner training as an essential element.

Family members are encouraged to:

- Participate in therapy sessions.

- Simplify language by using short, uncomplicated sentences.

- Repeat words or write down key words to clarify meaning as needed.

- Maintain a natural conversational manner appropriate for an adult.

- Minimize distractions, such as loud radio or TV.

- Include the person with aphasia in conversations.

- Ask for and value the opinion of the person with aphasia, especially regarding family matters.

- Encourage any type of communication, whether it is speech, gesture, pointing, or drawing.

- Avoid correcting the person's speech.

- Allow the person plenty of time to talk.

- Help the person become involved outside the home. Seek out support groups, such as stroke clubs, aphasia groups, intensive camps, and more.

Importantly, people with PPA often benefit from speech-language therapy. Thus, referrals to speech-language pathologists for people with PPA should always be made, not only for assistance with diagnosis but also for treatment.

What research is NIDCD supporting on aphasia?

NIDCD-funded research seeks to determine the nature, causes, treatment, and prevention of communication disorders, including aphasia. This research is critical because of the impact aphasia and PPA have on an individual’s ability to communicate and their overall health outcomes. Research helps us better understand aphasia and identify the most effective ways to support the success of individuals with aphasia.

Some NIDCD-funded research projects are focused on using advanced imaging methods to explore how language areas in the brain are structured and how the brain processes language as it recovers following stroke. This type of research may advance our knowledge of how the areas involved in using and understanding language reorganize after a brain injury. Researchers are testing new types of speech-language therapy in people with both recent and chronic aphasia to see if new methods can better help them recover word retrieval, grammar, conversation skills, and other aspects of language. Other research examines different ways to stimulate the brain through speech-language therapy to enhance outcomes.

Research on PPA addresses similar topics but with an additional focus on early detection, understanding how the brain changes throughout the course of the disease, effective speech-language treatments, and how communication skills can be better preserved as the disease progresses.

NIDCD-funded clinical trials are also testing other treatments for aphasia. A list of active NIDCD-funded aphasia trials can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Where can I find additional information about aphasia?

NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations providing information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

For more information, contact us at:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

Email: nidcdinfo@nidcd.nih.gov

NIH Pub. No. 97-4257

December 2024